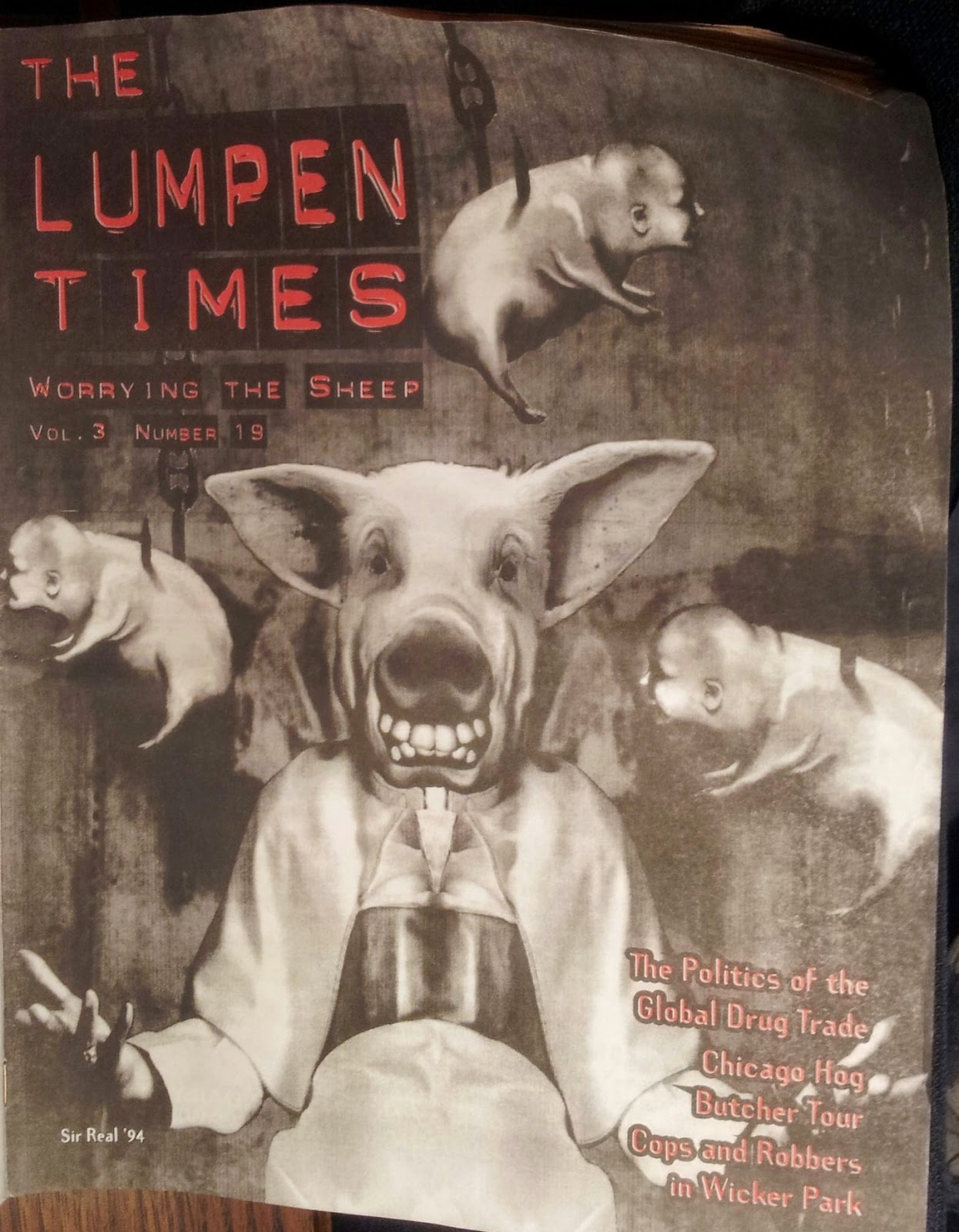

In July of 1994, I published a lengthy piece in the Lumpen Times, on the newly contentious topic of gentrification. At that time, Lumpen was a fledgling little magazine that had a large readership in a rather small geographical area, in and around Wicker Park. I called my journalistic style at that time dada-surrealist, with cut-and-paste as one organizing principle. "Cops and Robber Barons" largely focuses on the redlining practices of the banks, which helped pave the way for the resettling of Wicker Park in the '70s and '80s. I am not a statistician, and wading through hundreds, thousands of pages of microforms - microforms! at the library downtown, strained my math muscles to the limit. I found a lot of information startling, not for its content, we all know that banks are not ethical beacons, but for the clarity and stark picture of reality that emerged from this search through records made public through the Community Reinvestment Act and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. A large red line had been drawn around Westtown and Wicker Park, and hardly a dime was lent to any poor person or person of color, even for the most minimal of home improvement loans, for a few decades. And then, Wicker Park exploded, and it's as if a huge can of white paint was tipped over onto the intersection of North, Milwaukee, and Damen, with banks suddenly dumping tens of millions of dollars into the area.

Interspersed with that story, the text sadly overburdened with statistics presented by someone who loves numbers but was barely able to stay above water through thousands of pages of them, are vignettes about the wide variety of police abuses and instances of brutality that continue to pollute our communities today, particularly our poorer ones, as in Wicker Park in the '80s and '90s. There's a bit here and there about graffiti and its importance; at that time, I'd met quite a few writers, artists, and activists who used graffiti as their medium.

Some attention is paid to the psychology and public persona of the gentry. And, ultimately the question of the role of artists and writers in siding with the forces of oppression, or in creating a richer, more equitable world by siding with our neighbors, is the most important and where I ended my story, back then.

A week after publication, I was brutally assaulted by police in front of several hundred people (probably unrelated to the article, but who knows, that's a tale for another day), who had come outside to see what the commotion was all about as a bunch of us were violently arrested for making music at the six-corners in the new arts district. I'm not yet sure if that was a work of art, or not.

Cops

and Robber Barons

The

Truth in Lending Practices of Corrupt and Racist Chicago Banks

[we

wanna turn away from disturbing events, disturbing thoughts]

Last

summer I met a Puerto Rican man who gave me a quick literacy lesson

at the corner of North Avenue and California. He told me there's a cop in

Humboldt Park named Arceo who went into a Puerto Rican family's front

yard and started feeling the daughter's breasts while her mother

looked on in shock. The young woman resisted; the cop pushed her to

the ground, pinned her to the ground, face down. He then pulled her

shirt up over her head, held her hands behind her back …

Channel

26 and other Latino media reported on the event; it never made it

into white media. No public outcry from the Puerto Rican community

led to the dismissal of the cop.

The

man I talked with had a thousand stories like this one. He wrote

about it in the only media available to him: graffiti. He wrote the

cop's name upside down, repeatedly. This is a dis that cops

recognize.

[I

walk through Wicker Park looking for art this vital, this social. I

don't usually find it.]

Graffiti

is a vital form of communication in Chicago's ghettos. Although

Wicker Park and the larger West Town area are still a ghetto, with an

overall 32% poverty rate, the wealthier white settlers and the

settler mentality are taking over. The large FDS (“Fuck Da System”) that used to get

sprayed on the big brown Mussolini wall at Walgreens on Milwaukee got

replaced by the corporate-inspired, ominous-sounding “Follow Da

Leader” mural on the el ramp, cleansed of content and adrenalin.

I

use the term “settler” to define people who move into an area,

take over larger and larger spaces, and attempt to dominate that

area. Settlers view the natives, the preceding inhabitants, with

condescension, bigotry, hatred, brutality. Like Columbus, settlers

even try to blame the natives for the destruction of the indigenous

community. The recent spate of media attention from Spin,

Billboard, New York Times, and

Newsweek reinforce the

settler mentality in Wicker Park / West Town, consistently ignoring

the pre-existing communities.

The

settler mentality can't accept graffiti as legit. Graffiti's not

controllable, not in

the way that tamed and poised “art” is. It's associated with

“gangs.” And, most importantly, as Da Leader blabs in his “Mayor Daley's Graffiti Blasters”

pamphlet, “Graffiti is an ugly form of vandalism. It creates fear,

lowers property values ...” So

never fear, Wicker Park / West Town settler: Pilgrim Daley's military

sodablasting squads and graff squads are there for you, to

cover your unsightly

blemishes, your costly

devaluations. Nevermind the infant mortality, the police brutality,

the economic deprivation, the pain that lives in the Puerto Rican,

Mexican, African-American, and poor white communities that preceded

you.

Focusing

on graffiti's a joke in West Town. But the gentry's whole attack on

graffiti and young people of color makes sense – if turning a buck

through gentrification is the goal. Focusing on the physical

appearance of a neighborhood diverts attention away from root causes

of urban decay – state and institutional neglect and attack,

slumlording, and discriminatory lending practices.

[it's

hard to quantify pain and oppression: how much easier is it to cover

them up?]

I

went to another gentrification meeting at Near Northwest Arts Council

last fall. Various factions of settler society discussed

gentrification, the forced removal of people of color from Wicker

Park / West Town. The Old Milwaukee Avenue Chamber of Commerce gentry

were there, along with some white pioneers from the early Old Wicker

Park Committee days, a few artists (“It's important we be aware of

what impact we're having. This is the third neighborhood I've lived

in where gentrification is happening …” - To what end,

awareness?), small businesspeople like Gary Marx and Ken Corrigan,

and assorted anarchists and independents.

There

was no one from Wicker Park / West Town impacted most by settlerism

in the room. I couldn't get over the impression that the word

“gentrification” is overused and not understood. Overused by

settlers, understood by almost none of the low-income Latinos,

African-Americans, and poor whites I've ever talked with in this

neighborhood. Any discussion of the forced removal of the poor and

people of color that uses the “G” word is probably taking place

without our input and participation.

Ken

Corrigan suggested targeting the banks, rather than the “fronts”

of gentrification like the horrendous and distasteful Around the

Coyote and Bookseller's Row. I thought, “Man, you fuckin' do that.”

The meeting ended with a goon from Chicago Artists' Coalition calling

the now infamous and critical “Pound the Coyote” pamphlet

“fascist”; so much for dunderheaded arts organizations and

freedom of expression.

[there's

a town in England where in the old days only wealthy landowners could

live. It's called Gentry.]

When

we look into the root causes of the destruction of the West Town

Puerto Rican and Mexican communities and into the recent resettlement

by whites, it's inportant to look everywhere – macro, micro,

national, local, theoretical and practical, general and specific. As

in ghettos elsewhere, physical structures and property values in West

Town (bounded by the Chicago River on the east and Humboldt Park on

the west, Kinzie on the south and Bloomingdale on the north) decayed

when the wealthy decreed it. Loans to low-income people of color for

home improvement and purchase dwindled throughout the '70s and '80s.

In

general, West Town banks make a mocker of the idea of “fairness in

lending.” Research into local banks reveals an ugly, racist

approach to the people who lived here before the arrival of the new

settlers: this approach laid the foundation for resettlement.

I

recently stepped inside Manufacturers Bank for the first time since I

moved to West Town; the fresh graffiti on the sidewalk that read

“This Way to Gentrification” had already been scrubbed off.

I

recently stepped inside Manufacturers Bank for the first time since I

moved to West Town; the fresh graffiti on the sidewalk that read

“This Way to Gentrification” had already been scrubbed off.

Manufacturers

Bank sits in the geographical heart of Census Community Area 24, West

Town, and has no other facilities or branches outside of its 1200 N.

Ashland office. (It's also headquarters for West Town Community

Bankers. See below.) Its lending practices reflect the racist, class

and gender biases of our society, and of most area banks.

Manufacturers

Bank lent a mere 15% of its $6,671,000 total housing dollars in West

Town in 1992, the most recent year that data is available. Two-thirds

of that was lent to wealthy whites; this means that Manufacturers

Bank lent only $340,000, 5% of its total housing lending, to West

Town Latinos. Latinos make up 62% of West Town's population;

African-Americans 9%. If Manufacturers has an interest in West Town,

it's clear that it lies with the wealthier whites settling in.

African-Americans

can forget approaching Manufacturers for housing loans. The bank lent

a grand total of $7,000 to African-Americans in '92, 0.1% of its

lending; it lent $753,000 to Latinos, 11% of its housing lending.

Like

most West Town banks, Manufacturers Bank lent heavily to comfortable

and wealthy whites, most of whom live in the suburbs and other areas

that are 80% or more white. And, like most West Town banks,

Manufacturers made no FHA or VA loans.

At

another point of the “pleasantly dilapidated” Wicker Park

Bohemian Triangle (bounded by Division, Milwaukee, and Hoyne) sits

Fairfield Savings, whose lending practices show even less concern for

West Town communities. Fairfield lent over $12 million for housing in

'92; $60,000 of it, 0.5%, landed in West Town.

Fairfield

S&L (Damen Ave. and North) is a white man's bank. It lent Latinos

$196,000, 1.6% of its housing lending, in '92. Fairfield lent nothing

to African-Americans. Ninety-seven percent of its dollars went to

whites.

It's

clear that opposition to the forced removal of Puerto Ricans,

Mexicans, African-Americans, and poor whites from West Town must call

Manufacturers, Fairfield, and other banks to the carpet for their

role in ripening West Town for the invasion of the Old Wicker Park

Committee types and the gentry in general. See the accompanying chart

for further details.) By disinvesting in the community, and not

lending to low-income folks, Manufacturers and Fairfield made it

difficult for people to make repairs for code violations, or to

purchase the $10,000 home that existed here.

A

Mexican family I know applied to a West Town area bank for a loan to

purchase a house in Bucktown in the early '80s. The loan officer told

them that they needed 25% down. I don't know if that is common; I

doubt that it is. Obviously they didn't have the money. Today, they

are well aware that they'll have to move soon. If you don't have the

money and the right skin color, the banks won't give you a loan.

[the

Old Wicker Park Committee, the “fuck da poor” gang, embody the

settler mentality – condescending, arrogant, brutal.]

In

early April, Old Wicker Park Committeemen David Schabes and Robert

Gatz threw together a proposal for Clinton's Empowerment Zone Program

– the new “urban renewal.” (The original Urban Renewal led to

the destruction of many already-exploited urban communities in the

'50s and '60s.) Eager to exploit Census data indicating conditions of

extreme oppression in West Town, particularly among Latinos and

African-Americans, and no longer content with the gentrification of

the Bohemian Triangle, the gentlepeople of OWPC sought big federal

money to extend their bleached suburban dreamscape outward, westward,

Funding would likely have been used to further dislocate the very

people it purported to empower. Fortunately, it was rejected by the

City Council.

The

Bohemian Triangle acts as epicenter for the resettlement of West

Town. Census Tract 2414 lost 41% of its Latinos and 17% of its

African-Americans between 1980 and 1990; median rents increased 22%

beyond inflation; total housing unites decreased 3.7%. People in

Census Tract 2415 experienced 34% increases in rents, and a 16% drop

in Latinos. Housing stock fell 9.4%.

These

figures do not reflect general trends in West Town. West Town is

going through a period of depopulation, with a 30% drop to 1970 to

1990. The white population showed the only major change from 1980 to

1990, dropping 23% from 31,415 to 24,117. The influx of young artists

must not be keeping pace with the flight of Poles and Ukraines. As

the population of Latinos remained the same, and since the number of

housing units fell by 6.6%, people of color must be doubling up,

living in more cramped quarters.

The

Old Wicker Park Committee proposal, which gathered local gentry into

a West Town Coalition (WTC), reveals much about the settler's mindset

and worldview. It reads like an hallucinatory college textbook –

boring yet fantastic, the words seem to have no relation whatsoever

to the conditions and communities of West Town. Central to the West

Town Coalition proposal is the proposition that West Town residents

are “plagued by common and familiar urban and societal problems.”

Contrary

to West Town Coalition's assertions, ethnic groups do not share

common problems in West Town. It's hard to get a clear economic

picture from Census data, though, for this reason: in the population

figures, the number of Latinos is listed as a category separate from

the others, and people of Spanish descent are included in the other

categories. This throws of the economic data for each group.

For

example, the 1990 Census says that poverty status in West Town is as

follows: Latinos 37%, African-Americans 47%, whites 25.9%. But the

25.9% figure includes approximately 20,000 white Latinos,

bring the poverty percentage up for the category. A more realistic

figure is probably about 14%.

There's

an African-American man who often begs for change at

North/Milwaukee/Damen; often he has no place to sleep at night, and

few settlers offer to make room for him. A Puerto Rican friend of his

sometimes invites him over; he sleeps with 21 other Puerto Ricans in

a small apartment in Humboldt Park, with hammocks strung one above

another. Very few settlers face such overcrowding. Mexican immigrants

often face deportation at the hands of La Migra; settlers don't know

that fear. A few months ago, I saw a police car intentionally try to

hit a young Puerto Rican on Division St. for no reason; very few

settlers experience the police as an army of occupation. Levels of

infant mortality, AIDS, and unemployment are far lower in settler

society than in any community of color. These are not “common and

familiar” problems.

To

meet those “common problems,” the WTC proposal claims that West

Town has achieved and desires “to maintain a multiethnic community

together peaceably with mutual respect and appreciation in an

attractive and healthy environment with thriving commerce; stable

public and private investment; safety for people and property ...”

It's

impossible to “maintain” something which doesn't exist. Fear,

anger, and mute suspicion do not make for peace, respect, or

appreciation. A Puerto Rican mother packing to move knows a far

different “shared sense of the community's history” from the West

Town Coalition settler pushing her out the door, or the sheriff

tossing her belongings into the street.

Last

summer, a cop chased a young Latino through Wicker Park. He tackled

the young man, and pinned him to the ground. A lieutenant, who was

standing nearby, walked over and kicked the young man in the ribs. I

asked the Art Institute student I was talking to, and who had seen

the kick, if she wanted to go get the cop's name and badge number;

she said no, she had to go.

[our

tolerance for other people's pain increases with our distance from

the realities of their lives]

The

Old Wicker Park Committee's vision of West Town is the gentrifier's

vision: the “thriving commerce” it fawns over is the increasing

glut of settler businesses in the “already revitalizing commercial

district” at Damen, North, and Milwaukee. This vision essentially

demands the removal of low-income Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and

African-Americans – why else would the Old Wicker Park Committee

have opposed Deborah's Place, a shelter for homeless women? - and yet

the word displacement never enters into the WTC''s myopic vision or

its proposal as the overwhelming problem that it is.

Displacement

also affects low-income artists and writers, although to a far lesser

degree. Many whites in West Town think of themselves as “starving

artists,” while paying $13,000 a year for art school. Very few of

them actually live in conditions of poverty. Severty percent of the

children of single mothers in West Town live in poverty; some

actually are starving.

Last

year, I made about $7,500. I made ½ the median income for West Town

whites. I think I'm low-budget. Still, I made about $2,000 more than

the average Latino, and about $1,000 more than the average

African-American in West Town.

Within

the Bohemian Triangle, Census Tract 2414, whites made $19,552 per

capita in '90; this was almost four times the Latino per capita

income. In Census Tract 2415, bounded by Milwaukee, North, and

Ashland, Latinos had a poverty rate double that of whites, and made

about 1/3 as much per year. These trends, strongly influenced by the

new white settlement, make displacement likely, for as rents go up,

only the settlers can afford them.

The

Old Wicker Park Committee's West Town Coalition focuses heavily on

investment, service, cosmetic beautification, policing, and on bogus

notions of multiculturalism – with a smattering of liberal-sounding

concerns like housing, education, and culture thrown in.

Contradictions abound.

- At no point in WTC's proposal do the authors even acknowledge the existence of a distinct Puerto Rican community. Probably because their only contact with Puerto Ricans comes in statistics, which lump all Latinos together.

- WTC sees “a burgeoning arts community that acts as a magnet to public and private investment. Actually, there's no contradiction here; clear, concise, direct statement of the unity of settler art and money.

- It's clear who WTC wants in their “underutilized park spaces and facilities.” A few years ago, Old Wicker Park Committee pushed to get Wicker Park (the actual park) changed to “passive use.” “Passive use” is code for getting African-Americans off the basketball courts.

- WTC calls for “community policing,” which more effectively enlists residents as snitches. In a show of settler unity, some artists have joined block clubs that call the cops when the “natives” get restless. Old Wicker Park Committee and East Village Association (EVA is a WTC partner) have evolved close relations with Chicago Police District 13; Old Milwaukee Avenue Chamber of Commerce with District 14.

- The specter of “gang violence” promotes settler unity; talk of “gang elimination” sounds ominous. Yet according to 13th District Criminal Activity Reports for April '93, published in EVA's own newsletter, one out of 110 crimes committed that month was “gang-related.”

- WTC sees “family-oriented systems of values” in its vision of a healthy community; that's why they include Humboldt Christian School in their proposal. In addition to propagating anti-choice, anti-women views, such fundamentalist organizations are infecting Latino children's minds with profoundly idiotic, authoritarian tripe.

One

of the most telling contradictions in WTC's vision of West Town lies

in the participation of the West Town Community Bankers (WTCB) group.

WTCB “meets monthly to ascertain the needs of the West Town

Community and to develop the necessary services and products to meet

those needs.” With rare exception, the banks listed have shown no

interest in low- and moderate-income people of color. WTCB draws

banks like Manufacturers and Fairfield (see above) together with

other West Town banks, like 1st Security Savings on

Western Ave. In '92, 1st Security Savings lent over $34

million for housing; of this total, it lent a whopping $8,000 to

African-Americans in all Chicago; $1,887,000, or 5%, to Latinos.

Lending to whites exceeded $28 million, or 86%. Of the $7,486,000

lent in West Town, the majority went to whites.

Other

banks in West Town Community Bankers include Cole Taylor, Avondale

Federal Savings Bank, and Mid Town Bank and Trust, where Miles Berger

sits as Chairman of the Board. Mid Town made no housing loans to

African-Americans in '92 (see accompanying chart for details).

Recently,

there has been a shift in West Town lending, as indicated in WTC's

Empowerment Zone proposal. Like vultures, “several downtown banks

have expressed an interest in becoming part of the coalition.”

Drawn by the greed of speculation and resettlement of Wicker Park,

money has started to pour into West Town: Chicago banks dumped around

$10 million in Census Tract 2414 in '92 alone (other Tracts nearby

received a few hundred thousand, maybe a million or two). This money

fuels gentrification; it fuels the construction of the Candyland

pastel postmodern houses popping up all over. By inflating property

taxes in the surrounding area, this money drives poor people out.

WTC's

proposal is notable as much for who it excludes as for who it

includes. WTC identifies “existing groups with knowledgeable and

motivated individuals” as “community assets”; yet its list of

committed partners reads like a who's who of West Town gentry.

Across

the board, the WTC proposal excludes some of the most vital

organizations at work in West Town – Juan Antonio Corretjer Puerto

Rican Cultural Center and Campos Puerto Rican High School; Ruiz

Belvis Cultural Center; Autonomous Zone; and Centro Sin Fronteras.

It's no accident that all of these groups oppose the further removal

of the poor and people of color from West Town.

WTC's

proposal harks back to OWPC's successful efforts to get Wicker Park

designated in the National Registry of Historic Places in '79, and

city landmark status in '91. Although these distinctions lack the

driving force of real estate speculation and banking discrimination,

they certainly stoke the displacement machine: major renovations get

a 20% income tax credit from the feds; the state freezes property

taxes for eight years, with another four years of reductions.

As

the comprehensive anti-gentrification manual, Displacement: How to

Fight It says, “On the whole, historic preservation laws are

far more protective of buildings than of the tenants inside them ….

these efforts to conserve our historical heritage may winde up

imposing severe displacement costs on the lower-income people to whom

these buildings have 'trickled down'.”

I

talked one afternoon in Earwaxx with an architecture student new to

the area who marvelled at the mansions of Wicker Park. I told her of

the dozens of low-income Puerto Ricans who were pushed out of just

one mansion so that one small yuppie family could remake This Old

House. She said, “Yeah, but those poor people didn't appreciate

the architecture. The rehabbers are preserving beauty.”

[the

price of European-based notions of beauty exact a high toll from

people of color – forced exclusion, eviction, and displacement.]

Rent.

A

Mexican man I know moved to the Bucktown area in 1979; his rent was

$130 a month. Now he's married and has three children. The five of

them live in a small two-bedroom apartment that costs $400. Their

family income plummeted when the father had heart transplant surgery

and lost his job.

In

West Town, from '80 to '90, median rents jumped 66% beyond inflation,

from $138 to $383, while median family incomes fell 5.6% from $21,744

to $20,532. Compare this with Lincoln Park yuppie heaven, where rents

increased 43%, while family incomes skyrocketed 82%, from $41,077 to

$75,085. Or compare with the more stable far northside North Park,

where rents increased only 17.7%, while family incomes edged up 3.5%.

Statistics for all Chicago show only a 40% increase in rent, with a

slight 2.4% drop in income.

A

$600 apartment would cost the average West Town white family with two

kids 13% of its income. The same apartment would cost the same size

latino family 32% of its income. The white family would have to rent

a $1,500 apartment to spend 32% of its income on rent. Those $1,500

apartments are starting to pop up in West Town.

Clearly,

most people in West Town face crisis economic and social conditions,

conditions which gentrification and settlerism only exacerbate. New

developments like the single-family Candyland houses along Wabansia

between Damen and Ashland affect the surrounding area and its people

in hideous ways (beyond the visually hideous). The owner of a

Bucktown 3-flat recently told me that when his property taxes tripled

in one year, he got back down to earth by passing the costs on to his

tenants, whose ropes tightened. This pattern repeats all around West

Town.

There's

a tendency among the new settlers of West Town – among speculators,

artists, even among some progressives and radicals – to look upon

poor people as colorful backdrop to our activities, whether

financial, artistic, personal, or political. I have done this.

There's

a tendency among the new settlers of West Town – among speculators,

artists, even among some progressives and radicals – to look upon

poor people as colorful backdrop to our activities, whether

financial, artistic, personal, or political. I have done this.

Until

we wake up to our own collusion with powerful downtown interests, we

will at best continue to make idle proclamations against white

invasion, unable to build community for ourselves and with others.

In

the late '60s, the federal Kerner Commission Report suggested that

high concentrations of oppressed people near the cities' financial

centers caused the uprisings that shook the gentry. Since then, in

cities from Seattle to Boston to Chicago, efforts to move poor people

to the outskirts, on the model of South American cities ringed with

shantytowns, continue to wreak havoc on African-American, Chicano,

Mexican, Puerto Rican, poor white, and other communities. Like

Seattle, alternative music and art are doing the dirty work of the

gentry in West Town, making ghettos safe for the gentry to reclaim

the inner city. Like Columbus sailing the ocean blue, we explore

Milwaukee Avenue …

Recent

activity against Around the Coyote marks a turning point in the

settling of Wicker Park / West Town – many people are opening up

new avenues of creativity and expression that welcome dissent,

instead of trying to clamp down on it. It's vital that artists,

writers, and musicians work with the raw substance of life around us,

with the people around us, rather than merely or only turning inward, rather than

joining settler block clubs and neighborhood watches.

****

Some Sources

Culture

and Imperialism. Edward Said.

1994.

Displacement:

How to Fight It. Chester

Hartman, et al. Legal Services Anti-Displacement Project. 1981.

Home

Mortgage Disclosure Act microforms.

Located at Harold Washington Library, 5th

Floor, Gov't Publications Dept. 1992.

Settlers:

The Mythology of the White Proletariat: an anti-racist story of the

U.S. J. Sakai. Morningstar

Press, Chicago. 1989.

U.S.

Census. 1980 and 1990.

No comments:

Post a Comment